problem

stringlengths 2

6.28k

| solution

stringlengths 0

13.5k

| answer

stringlengths 1

97

| problem_type

stringclasses 9

values | question_type

stringclasses 5

values | problem_is_valid

stringclasses 5

values | solution_is_valid

stringclasses 4

values | source

stringclasses 8

values | synthetic

bool 1

class |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

VI OM - II - Task 3

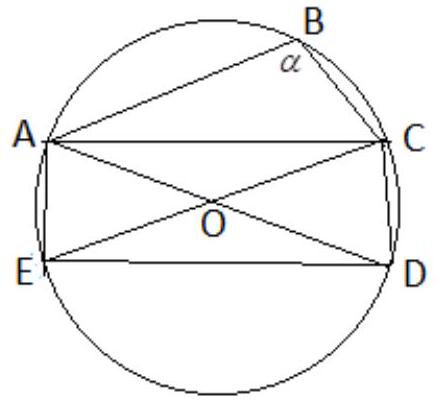

What should be the angle at the vertex of an isosceles triangle so that a triangle can be constructed with sides equal to the height, base, and one of the remaining sides of this isosceles triangle? | We will adopt the notations indicated in Fig. 9. A triangle with sides equal to $a$, $c$, $h$ can be constructed if and only if the following inequalities are satisfied:

Since in triangle $ADC$ we have $a > h$, $\frac{c}{2} + h > a$, the first two of the above inequalities always hold, so the necessary and sufficient condition for the existence of a triangle with sides $a$, $c$, $h$ is the inequality

From triangle $ADC$ we have $h = a \cos \frac{x}{2}$, $\frac{c}{2} = a \sin \frac{x}{2}$; substituting into inequality (1) gives

or

and since $\frac{x}{4} < 90^\circ$, the required condition takes the form

or

Approximately, $4 \arctan -\frac{1}{2} \approx 106^\circ$ (with a slight deficit). | 106 | Geometry | math-word-problem | Yes | Yes | olympiads | false |

IX OM - II - Task 2

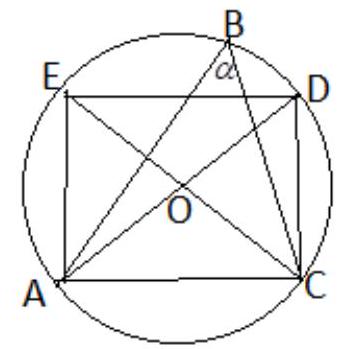

Six equal disks are placed on a plane in such a way that their centers lie at the vertices of a regular hexagon with a side equal to the diameter of the disks. How many rotations will a seventh disk of the same size make while rolling externally on the same plane along the disks until it returns to its initial position? | Let circle $K$ with center $O$ and radius $r$ roll without slipping on a circle with center $S$ and radius $R$ (Fig. 16). The rolling without slipping means that different points of one circle successively coincide with different points of the other circle, and in this correspondence, the length of the arc between two points of one circle equals the length of the arc between the corresponding points of the other circle.

Consider two positions $K$ and $K_1$ of the moving circle, corresponding to centers $O$ and $O_1$ and points of tangency with the fixed circle $A$ and $B_1$; let $B$ be the point on the circumference of circle $K$ that, in the new position, passes to the point of tangency $B_1$, and let $\alpha$ and $\beta$ denote the radian measures of angles $ASB_1$ and $AOB$. Since the length of arc $AB_1$ of the fixed circle equals the length of arc $AB$ of the moving circle, we have $R \alpha = r \beta$. The radius $OA$ of the moving circle will take the new position $O_1A_1$, with $\measuredangle A_1O_1B_1 = \measuredangle AOB = \beta$. Draw the radius $O_1A_0$ parallel to $OA$; we get $\measuredangle A_0O_1B_1 = \measuredangle ASB_1 = \alpha$. The angle $A_0O_1A_1 = \alpha + \beta$ is equal to the angle through which circle $K$ has rotated when moving from position $K$ to position $K_1$. If $R = r$, then $\beta = \alpha$, and the angle of rotation is then $2 \alpha$.

Once the above is established, it is easy to answer the posed question.

The moving disk $K$ rolls successively on six given disks; the transition from one to another occurs at positions where disk $K$ is simultaneously tangent to two adjacent fixed disks. Let $K_1$ and $K_2$ be the positions where disk $K$ is tangent to fixed disk $N$ and to one of the adjacent disks (Fig. 17). Then $\measuredangle O_1SO_2 = 120^\circ$, so when moving from position $K_1$ to position $K_2$, the disk rotates by $240^\circ$. The disk will return to its initial position after $6$ such rotations, having rotated a total of $6 \cdot 240^\circ = 4 \cdot 360^\circ$, i.e., it will complete $4$ full rotations.

Note. We can more generally consider the rolling of a disk with radius $r$ on any curve $C$ (Fig. 18). When the point of tangency $A$ traverses an arc $AB_1$ of length $l$ on the curve, the angle through which the disk rotates is $\alpha + \beta$, where $\alpha$ is the angle between the lines $OA$ and $O_1B_1$, i.e., the angle between the normals to the curve $C$ at points $A$ and $B$, and $\beta = \frac{l}{r}$. | 4 | Geometry | math-word-problem | Yes | Yes | olympiads | false |

XXXVI OM - III - Problem 1

Determine the largest number $ k $ such that for every natural number $ n $ there are at least $ k $ natural numbers greater than $ n $, less than $ n+17 $, and coprime with the product $ n(n+17) $. | We will first prove that for every natural number $n$, there exists at least one natural number between $n$ and $n+17$ that is coprime with $n(n+17)$.

In the case where $n$ is an even number, the required property is satisfied by the number $n+1$. Of course, the numbers $n$ and $n+1$ are coprime. If a number $d > 1$ were a common divisor of $n+1$ and $n+17$, then it would divide the difference $(n+17)-(n+1) = 16$, and thus would be an even number. However, since $n+1$ is an odd number, such a $d$ does not exist. Therefore, the numbers $n+1$ and $n(n+17)$ are coprime.

In the case where $n$ is an odd number, the required property is satisfied by the number $n + 16$. Indeed, the numbers $n+16$ and $n+17$ are coprime. Similarly, as above, we conclude that $n$ and $n+16$ are also coprime. Therefore, $n+16$ and $n(n+17)$ are coprime.

In this way, we have shown that $k \geq 1$.

Consider the number $n = 16!$. The numbers $n+2, n+3, \ldots, n+16$ are not coprime with $n(n+17)$, because for $j = 2, 3, \ldots, 16$, the numbers $n+j$ and $n$ are divisible by $j$. Only the number $n+1$ is coprime with $n(n+17)$. From this example, it follows that $k \leq 1$. Therefore, $k = 1$. | 1 | Number Theory | math-word-problem | Yes | Yes | olympiads | false |

XXXVIII OM - III - Zadanie 5

Wyznaczyć najmniejszą liczbę naturalną $ n $, dla której liczba $ n^2-n+11 $ jest iloczynem czterech liczb pierwszych (niekoniecznie różnych).

|

Niech $ f(x) = x^2-x+11 $. Wartości przyjmowane przez funkcję $ f $ dla argumentów całkowitych są liczbami całkowitymi niepodzielnymi przez $ 2 $, $ 3 $, $ 5 $, $ 7 $. Przekonujemy się o tym badając reszty z dzielenia $ n $ i $ f(n) $ przez te cztery początkowe liczby pierwsze:

\begin{tabular}{lllll}

&\multicolumn{4}{l}{Reszty z dzielenia:}\\

&przez 2&przez 3&przez 5&przez 7\\

$ n $&0 1&0 1 2 &0 1 2 3 4&0 1 2 3 4 5 6\\

$ f(n) $&1 1&2 2 1&1 1 3 2 3& 4 4 6 3 2 3 6

\end{tabular}

Zatem dowolna liczba $ N $ będąca wartością $ f $ dla argumentu naturalnego i spełniająca podany w zadaniu warunek musi mieć postać $ N = p_1p_2p_3p_4 $, gdzie czynniki $ p_i $ są liczbami pierwszymi $ \geq 11 $.

Najmniejsza z takich liczb $ N= 11^4 $ prowadzi do równania kwadratowego $ x^2-x+11=11^4 $ o pierwiastkach niewymiernych. Ale już druga z kolei $ N = 11^3 \cdot 13 $ jest równa wartości $ f(132) $. Funkcja $ f $ jest ściśle rosnąca w przedziale $ \langle 1/2; \infty) $ wobec czego znaleziona minimalna możliwa wartość $ N $ wyznacza minimalną możliwą wartość $ n $. Stąd odpowiedź: $ n = 132 $.

| 132 | Number Theory | math-word-problem | Yes | Yes | olympiads | false |

XII OM - II - Task 4

Find the last four digits of the number $ 5^{5555} $. | \spos{1} We will calculate a few consecutive powers of the number $ 5 $ starting from $ 5^4 $:

It turned out that $ 5^8 $ has the same last four digits as $ 5^4 $, and therefore the same applies to the numbers $ 5^9 $ and $ 5^5 $, etc., i.e., starting from $ 5^4 $, two powers of the number $ 5 $, whose exponents differ by a multiple of $ 4 $, have the same last four digits. The number $ 5^{5555} = 5^{4\cdot 1388+3} $ therefore has the same last $ 4 $ digits as the number $ 5^7 $, i.e., the digits $ 8125 $. | 8125 | Number Theory | math-word-problem | Yes | Yes | olympiads | false |

XVIII OM - II - Problem 4

Solve the equation in natural numbers

Note: The equation itself is not provided in the original text, so it is not included in the translation. | Suppose that the triple $(x, y, z)$ of natural numbers satisfies equation (1). After dividing both sides of equation (1) by $xyz$ we get

One of the numbers $x$, $y$, $z$ is less than $3$; for if $x \geq 3$, $y \geq 3$, $z \geq 3$, then the left side of equation (2) is $\leq 1$, while the right side is $> 1$.

If $x < 3$, then one of the following cases occurs:

a) $x = 1$; from equation (1) it follows that

b) $x = 2$; from equation (1) we get $2y + yz + 2z = 2 yz + 2$, hence

Therefore, $y-2 = 1$, $z-2 = 2$ or $y-2 = 2$, $z-2 = 1$, i.e., $y = 3$, $z = 4$ or $y = 4$, $z = 3$.

Analogous solutions are obtained assuming that $y = 2$ or that $z = 2$.

Equation (1) thus has $7$ solutions in natural numbers:

Note: Since

equation (1) is equivalent to the equation

which, after substituting $x-1 = X$, $y -1 = Y$, $z-1 = Z$, takes the form

The solution of equation (1b) in natural numbers was the subject of No. 9 in the XVII Mathematical Olympiad. | 7 | Number Theory | math-word-problem | Incomplete | Yes | olympiads | false |

III OM - I - Task 4

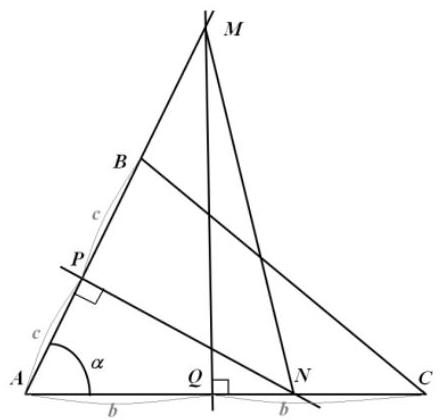

a) Given points $ A $, $ B $, $ C $ not lying on a straight line. Determine three mutually parallel lines passing through points $ A $, $ B $, $ C $, respectively, so that the distances between adjacent parallel lines are equal.

b) Given points $ A $, $ B $, $ C $, $ D $ not lying on a plane. Determine four mutually parallel planes passing through points $ A $, $ B $, $ C $, $ D $, respectively, so that the distances between adjacent parallel planes are equal. | a) Suppose that the lines $a$, $b$, $c$ passing through points $A$, $B$, $C$ respectively and being mutually parallel satisfy the condition of the problem, that is, the distances between adjacent parallel lines are equal. Then the line among $a$, $b$, $c$ that lies between the other two is equidistant from them. Let this line be, for example, line $b$. In this case, points $A$ and $C$ are equidistant from line $b$ and lie on opposite sides of it; therefore, line $b$ intersects segment $AC$ at its midpoint $M$. From the fact that points $A$, $B$, $C$ do not lie on a straight line, it follows that point $M$ is different from point $B$.

Hence the construction: we draw line $b$ through point $B$ and through the midpoint $M$ of segment $AC$, and then we draw through points $A$ and $C$ lines $a$ and $c$ parallel to line $b$ (Fig. 12). The parallel lines $a$, $b$, $c$ determined in this way solve the problem, since points $A$ and $C$, and thus lines $a$ and $c$, are equidistant from line $b$ and lie on opposite sides of this line.

We found the above solution assuming that among the sought lines $a$, $b$, $c$, the line $b$ lies between lines $a$ and $c$; since the "inner" line can equally well be $a$ or $c$, the problem has three solutions.

b) Suppose that the planes $\alpha$, $\beta$, $\gamma$, $\delta$, passing through points $A$, $B$, $C$, $D$ respectively and being mutually parallel, satisfy the condition of the problem, that is, the distances between adjacent planes are equal. Let these planes be in the order $\alpha$, $\beta$, $\gamma$, $\delta$. We mean by this that plane $\beta$ is equidistant from planes $\alpha$ and $\gamma$, and plane $\gamma$ is equidistant from planes $\beta$ and $\delta$.

In this case, points $A$ and $C$ are equidistant from plane $\beta$ and lie on opposite sides of it, so plane $\beta$ passes through the midpoint $M$ of segment $AC$. Similarly, plane $\gamma$ passes through the midpoint $N$ of segment $BD$. From the fact that points $A$, $B$, $C$, $D$ do not lie in a plane, it follows that point $M$ is different from point $B$, and point $N$ is different from point $C$.

From this, we derive the following construction. We connect point $B$ with the midpoint $M$ of segment $AC$, and point $C$ with the midpoint $N$ of segment $BD$ (Figure 13 shows a parallel projection of the figure). Lines $BM$ and $CN$ are skew; if they lay in the same plane, then points $A$, $B$, $C$, $D$ would lie in the same plane, contrary to the assumption. We know from stereometry that through two skew lines $BM$ and $CN$ one can draw two and only two parallel planes $\beta$ and $\gamma$.

To do this, we draw through point $M$ a line $m$ parallel to line $CN$, and through point $N$ a line $n$ parallel to line $BM$; plane $\beta$ is then determined by lines $m$ and $BM$, and plane $\gamma$ by lines $n$ and $CN$.

Finally, we draw through points $A$ and $D$ planes $\alpha$ and $\delta$ parallel to planes $\beta$ and $\gamma$; we can determine them, as indicated in Figure 13, by drawing through each of points $A$ and $D$ lines parallel to lines $BM$ and $CN$.

The planes $\alpha$, $\beta$, $\gamma$, $\delta$ determined in this way solve the problem, since points $A$ and $C$, and thus planes $\alpha$ and $\gamma$, are equidistant from plane $\beta$ and lie on opposite sides of this plane - and similarly, planes $\beta$ and $\delta$ are equidistant from plane $\gamma$ and lie on opposite sides of this plane.

We found the above solution assuming that the sought planes are in the order $\alpha$, $\beta$, $\gamma$, $\delta$. For other orders of the sought planes, we will find other solutions in the same way. The number of all possible orders, or permutations of the letters $\alpha$, $\beta$, $\gamma$, $\delta$, is $4!$, i.e., $24$. However, note that two "reverse" permutations, such as $\alpha$, $\beta$, $\gamma$, $\delta$ and $\delta$, $\gamma$, $\beta$, $\alpha$, give the same solution. Therefore, the problem has $\frac{24}{2} = 12$ solutions corresponding to the permutations. | 12 | Geometry | math-word-problem | Yes | Yes | olympiads | false |

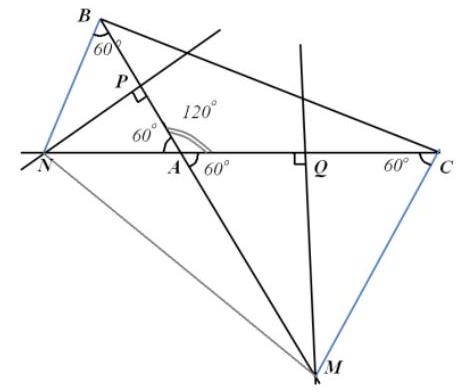

L OM - I - Task 3

In an isosceles triangle $ ABC $, angle $ BAC $ is a right angle. Point $ D $ lies on side $ BC $, such that $ BD = 2 \cdot CD $. Point $ E $ is the orthogonal projection of point $ B $ onto line $ AD $. Determine the measure of angle $ CED $. | Let's complete the triangle $ABC$ to a square $ABFC$. Assume that line $AD$ intersects side $CF$ at point $P$, and line $BE$ intersects side $AC$ at point $Q$. Since

$ CP= \frac{1}{2} CF $. Using the perpendicularity of lines $AP$ and $BQ$ and the above equality, we get $ CQ= \frac{1}{2} AC $, and consequently $ CP=CQ $. Points $C$, $Q$, $E$, $P$ lie on the same circle, from which $ \measuredangle CED =\measuredangle CEP =\measuredangle CQP = 45^\circ $. | 45 | Geometry | math-word-problem | Yes | Yes | olympiads | false |

LX OM - III - Zadanie 2

Let $ S $ be the set of all points in the plane with both coordinates being integers. Find

the smallest positive integer $ k $ for which there exists a 60-element subset of the set $ S $

with the following property: For any two distinct elements $ A $ and $ B $ of this subset, there exists a point

$ C \in S $ such that the area of triangle $ ABC $ is equal to $ k $. | Let $ K $ be a subset of the set $ S $ having for a given number $ k $ the property given in the problem statement.

Let us fix any two different points $ (a, b), (c, d) \in K $. Then for some integers

$ x, y $ the area of the triangle with vertices $ (a, b) $, $ (c, d) $, $ (x, y) $ is $ k $, i.e., the equality

$ \frac{1}{2}|(a - c)(y - d) - (b - d)(x - c)| = k $ holds. From this, we obtain the condition that the equation

has for any fixed and different $ (a, b), (c, d) \in K $ a solution in integers $ x, y $.

We will prove that if the number $ m $ does not divide $ 2k $, then the set $ K $ has no more than $ m^2 $ elements.

To this end, consider pairs $ (a \mod m, b \mod m) $ of residues of the coordinates of the points of the set $ K $ modulo $ m $.

There are $ m^2 $ of them, so if $ |K| > m^2 $, then by the pigeonhole principle, we will find two different points

$ (a, b) \in K $ and $ (c, d) \in K $ such that $ a \equiv c \mod m $ and $ b \equiv d \mod m $. For such points,

the equation (1) has no solution, since the left side of the equation for any $ x $ and $ y $ is divisible by $ m $,

while the right side is not. Therefore, $ |K| \leqslant m^2 $ for any $ m $ that is not a divisor of $ 2k $.

From the above considerations, it follows that if $ |K| = 60 $, then $ 2k $ must be divisible by all numbers

$ m \leqslant 7 $, since $ 60 > 7^2 $. It is easy to check that the smallest natural number divisible by

2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 is $ 2^2 \cdot 3 \cdot 5 \cdot 7 = 420 $, so $ 210|k $.

We will show that for every $ k $ such that $ 210|k $, a 60-element set $ K $ having the property given in the problem statement can be constructed. Let $ K $ be the set of all elements of the set $ S $,

whose both coordinates are in the set $ \{0, 1,..., 7\} $. Fix any two different points

$ A =(a, b) $ and $ B=(c, d) $ from the set $ K $. Then $ a - c, b - d \in \{-7, -6,..., 6, 7\} $, so if

$ a \neq c $, then $ a-c|420 $ and if $ b = d $, then $ b-d|420 $. Without loss of generality, we can assume that $ b = d $.

Then $ b - d|2k $, since $ 420|2k $. The point $ C =(c + \frac{2k}{d-b} ,d) $ is therefore an element of the set $ S $,

and the area of the triangle $ ABC $ is

Moreover, $ |K| = 60 $. As the set $ K $, we can take any 60-element subset of the set $ K $.

Thus, we have shown that a 60-element set having the desired property exists only for positive integers $ k $

that are multiples of 210. The smallest such number is 210. | 210 | Geometry | math-word-problem | Yes | Yes | olympiads | false |

LV OM - III - Task 5

Determine the maximum number of lines in space passing through a fixed point and such that any two intersect at the same angle. | Let $ \ell_1,\ldots,\ell_n $ be lines passing through a common point $ O $. A pair of intersecting lines determines four angles on the plane containing them: two vertical angles with measure $ \alpha \leq 90^\circ $ and the other two angles with measure $ 180^\circ - \alpha $. According to the assumption, the value of $ \alpha $ is the same for every pair $ \ell_i, \ell_j $.

Consider a sphere $ S $ centered at $ O $ with an arbitrary radius, and denote by $ A_i $, $ B_i $ the points of intersection of the line $ \ell_i $ with this sphere. Each of the segments $ A_iA_j $, $ A_iB_j $, $ B_iB_j $ (for $ i \neq j $) is a chord of the sphere $ S $, determined by a central angle of measure $ \alpha $ or $ 180^\circ - \alpha $. Therefore, these segments have at most two different lengths $ a $ and $ b $.

Fix the notation so that $ \measuredangle A_iOA_n = \alpha $ for $ i = 1,\ldots,n-1 $. Then the points $ A_1, \ldots, A_{n-1} $ lie on a single circle (lying in a plane perpendicular to the line $ \ell_n $). Let $ A_1C $ be the diameter of this circle. Each of the points $ A_2,\ldots,A_{n-1} $ is at a distance $ a $ or $ b $ from the point $ A_1 $; hence, on each of the two semicircles with endpoints $ A_1 $ and $ C $, there are at most two points from the set $ \{A_2,\ldots ,A_{n-1}\} $. Therefore, this set has at most four elements; which means that $ n \leq 6 $.

On the other hand, if $ n = 6 $, we can place the points $ A_1,A_2,\ldots,A_5 $ at the vertices of a regular pentagon, and the plane of this pentagon at such a distance from the point $ A_6 $ that these six points, together with their antipodal points $ B_1,\ldots,B_6 $, are the vertices of a regular icosahedron. The segments $ A_iB_i $ (diameters of the sphere $ S $) connect opposite vertices of this icosahedron and any two of them form the same angle. Therefore, $ n = 6 $ is the largest possible number of lines $ \ell_i $. | 6 | Geometry | math-word-problem | Yes | Yes | olympiads | false |

XXVI - I - Problem 9

Calculate the limit

| For any natural numbers $ k $ and $ n $, where $ n \leq k $, we have

In particular, $ \displaystyle \binom{2^n}{n} \leq (2^n)^n = 2^{n^2} $. By the binomial formula, we have

and hence $ \displaystyle 2^n > \frac{n^2}{24} $. Therefore,

Since $ \displaystyle \lim_{n \to \infty} \frac{1}{n}= 0 $, it follows that $ \displaystyle \lim_{n \to \infty} \frac{1}{2^n} \log \binom{2^n}{n}= 0 $. | 0 | Calculus | math-word-problem | Incomplete | Yes | olympiads | false |

XVI OM - II - Task 4

Find all prime numbers $ p $ such that $ 4p^2 +1 $ and $ 6p^2 + 1 $ are also prime numbers. | To solve the problem, we will investigate the divisibility of the numbers \( u = 4p^2 + 1 \) and \( v = 6p^2 + 1 \) by \( 5 \). It is known that the remainder of the division of the product of two integers by a natural number is equal to the remainder of the division of the product of their remainders by that number. Based on this, we can easily find the following:

\begin{center}

When \( p \equiv 0 \pmod{5} \), then \( u \equiv 1 \pmod{5} \), \( v \equiv 1 \pmod{5} \);\\

When \( p \equiv 1 \pmod{5} \), then \( u \equiv 0 \pmod{5} \), \( v \equiv 2 \pmod{5} \);\\

When \( p \equiv 2 \pmod{5} \), then \( u \equiv 2 \pmod{5} \), \( v \equiv 0 \pmod{5} \);\\

When \( p \equiv 3 \pmod{5} \), then \( u \equiv 2 \pmod{5} \), \( v \equiv 0 \pmod{5} \);\\

When \( p \equiv 4 \pmod{5} \), then \( u \equiv 0 \pmod{5} \), \( v \equiv 2 \pmod{5} \).\\

\end{center}

From the above, it follows that the numbers \( u \) and \( v \) can both be prime numbers only when \( p \equiv 0 \pmod{5} \), i.e., when \( p = 5 \), since \( p \) must be a prime number. In this case, \( u = 4 \cdot 5^2 + 1 = 101 \), \( v = 6 \cdot 5^2 + 1 = 151 \), so they are indeed prime numbers.

Therefore, the only solution to the problem is \( p = 5 \). | 5 | Number Theory | math-word-problem | Yes | Yes | olympiads | false |

XXXVI OM - I - Zadanie 9

W urnie jest 1985 kartek z napisanymi liczbami 1,2,3,..., 1985, każda lczba na innej kartce. Losujemy bez zwracania 100 kartek. Znaleźć wartość oczekiwaną sumy liczb napisanych na wylosowanych kartkach.

|

Losowanie $ 100 $ kartek z urny zawierającej $ 1985 $ kartek można interpretować jako wybieranie $ 100 $-elementowego podzbioru zbioru $ 1985 $-elementowego. Zamiast danych liczb $ 1985 $ i $ 100 $ weźmy dowolne liczby naturalne $ n $ i $ k $, $ n \geq k $. Dla dowolnego $ k $-elementowego zbioru $ X $ będącego podzbiorem zbioru $ Z = \{1,2,\ldots,n\} $ oznaczmy przez $ s(X) $ sumę liczb w zbiorze $ X $. Ponumerujmy wszystkie $ k $-elementowe podzbiory $ Z $ liczbami od $ 1 $ do $ ???????????????? = \binom{n}{k}: X_1, \ldots, X_N $. Wybieramy losowo jeden z tych zbiorów. Prawdopodobieństwo każdego wyboru jest takie samo, a więc równa się $ p = 1 /N $. Wartość oczekiwana sumy liczb w tym zbiorze równa się

Policzymy, w ilu zbiorach $ X_i $ występuje dowolnie ustalona liczba $ x \in Z $. Liczbie $ x $ towarzyszy w każdym z tych zbiorów $ k-1 $ liczb dowolnie wybranych ze zbioru $ Z-\{x\} $. Możliwości jest $ M = \binom{n-1}{k-1} $. Wobec tego każda

liczba $ x \in Z $ występuje w $ M $ zbiorach $ X_i $; tak więc w sumie każdy składnik $ x \in Z $ pojawia się $ M $ razy. Stąd $ s = M(1 + 2+ \ldots+n) = Mn(n+1)/2 $ i szukana wartość oczekiwana wynosi

W naszym zadaniu $ n = 1985 $, $ k = 100 $, zatem $ E = 99 300 $.

| 99300 | Combinatorics | math-word-problem | Yes | Yes | olympiads | false |

LII OM - I - Task 4

Determine whether 65 balls with a diameter of 1 can fit into a cubic box with an edge of 4. | Answer: It is possible.

The way to place the balls is as follows.

At the bottom of the box, we place a layer consisting of 16 balls. Then we place a layer consisting of 9 balls, each of which is tangent to four balls of the first layer (Fig. 1 and 2). The third layer consists of 16 balls that are tangent to the balls of the second layer (Fig. 4 and 5). Similarly, we place two more layers (Fig. 6).

om52_1r_img_2.jpg

om52_1r_img_3.jpg

om52_1r_img_4.jpg

In total, we have placed $ 16 + 9 + 16 + 9 + 16 = 66 $ balls. It remains to calculate how high the fifth layer reaches.

om52_1r_img_5.jpg

om52_1r_img_6.jpg

om52_1r_img_7.jpg

Let's choose any ball from the second layer; this ball is tangent to four balls of the first layer. The centers of these five balls are the vertices of a regular square pyramid, each edge of which has a length of 1 (Fig. 3). By the Pythagorean theorem, the height of this pyramid is $ \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} $. Therefore, the highest point that the fifth layer reaches is at a distance of $ \frac{1}{2} + 4 \cdot \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} + \frac{1}{2} = 1 + 2\sqrt{2} < 4 $ from the base plane. The 66 balls placed in this way fit into a cubic box with an edge of 4. | 66 | Geometry | math-word-problem | Yes | Yes | olympiads | false |

XXI OM - III - Task 6

Find the smallest real number $ A $ such that for every quadratic trinomial $ f(x) $ satisfying the condition

the inequality $ f.

holds. | Let the quadratic trinomial $ f(x) = ax^2 + bx + c $ satisfy condition (1). Then, in particular, $ |f(0)| \leq 1 $, $ \left| f \left( \frac{1}{2} \right) \right| \leq 1 $, and $ |f(1)| \leq 1 $.

Since

and

thus

Therefore, $ A \leq 8 $.

On the other hand, the quadratic trinomial $ f(x) = -8x^2 + 8x - 1 $ satisfies condition (1), which can be easily read from its graph (Fig. 15). Moreover, $ f. Thus, $ A \geq 8 $.

The sought number $ A $ is therefore equal to $ 8 $. | 8 | Inequalities | math-word-problem | Incomplete | Yes | olympiads | false |

L OM - I - Task 5

Find all pairs of positive integers $ x $, $ y $ satisfying the equation $ y^x = x^{50} $. | We write the given equation in the form $ y = x^{50/x} $. Since for every $ x $ being a divisor of $ 50 $, the number on the right side is an integer, we obtain solutions of the equation for $ x \in \{1,2,5,10,25,50\} $. Other solutions of this equation will only be obtained when $ x \geq 2 $ and for some $ k \geq 2 $, the number $ x $ is simultaneously the $ k $-th power of some natural number and a divisor of the number $ 50k $. If $ p $ is a prime divisor of such a number $ x $, then $ p^k|50^k $. Since $ p^k > k $, it cannot be that $ p^k|k $, so $ p \in \{2,5\} $. If $ p = 2 $, then $ 2^k|2k $, from which $ k = 2 $. If, however, $ p = 5 $, then $ 5^k|25k $, from which again $ k = 2 $. Therefore, $ x $ must simultaneously be the square of some natural number and a divisor of the number $ 100 $.

We obtain two new values of $ x $ in this case: $ x = 4 $ and $ x = 100 $. Thus, the given equation has 8 solutions: | 8 | Number Theory | math-word-problem | Yes | Yes | olympiads | false |

VI OM - II - Task 2

Find the natural number $ n $ knowing that the sum

is a three-digit number with identical digits. | A three-digit number with identical digits has the form $ 111 \cdot c = 3 \cdot 37 \cdot c $, where $ c $ is one of the numbers $ 1, 2, \ldots, 9 $, and the sum of the first $ n $ natural numbers is $ \frac{1}{2} n (n + 1) $, so the number $ n $ must satisfy the condition

Since $ 37 $ is a prime number, one of the numbers $ n $ and $ n+1 $ must be divisible by $ 37 $. There are two possible cases:

a) $ n = 37 k $, where $ k $ is a natural number; equation (1) then gives

The right side here is at most $ 54 $, so the number $ k $ can be at most $ 1 $, i.e., $ n = 37 $. This value, however, is not a solution to the problem, as $ \frac{1}{2} n (n + 1) $ then equals $ 37 \cdot 19 = 703 $.

b) $ n + 1 = 37 k $ ($ k $ = natural number); equation (1) gives $ (37 k - 1) k = 2 \cdot 3 \cdot c $.

The only possible value for $ k $ is similarly to a) the number $ 1 $, in which case $ n = 36 $ and $ \frac{1}{2} n(n + 1) = 18 \cdot 37 = 666 $. Therefore, the only solution to the problem is $ n = 36 $. | 36 | Number Theory | math-word-problem | Incomplete | Yes | olympiads | false |

XXXIX OM - I - Problem 1

For each positive number $ a $, determine the number of roots of the polynomial $ x^3+(a+2)x^2-x-3a $. | Let's denote the considered polynomial by $ F(x) $. A polynomial of the third degree has at most three real roots. We will show that the polynomial $ F $ has at least three real roots - and thus has exactly three real roots (for any value of the parameter $ a > 0 $).

It is enough to notice that

If a continuous function with real values takes values of different signs at two points, then at some point in the interval bounded by these points, it takes the value zero (Darboux property).

Hence, in each of the intervals $ (-a-3; -2) $, $ (-2; 0) $, $ (0; 2) $, there is a root of the polynomial $ F $. | 3 | Algebra | math-word-problem | Yes | Yes | olympiads | false |

XXIV OM - II - Problem 3

Let $ f:\mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R} $ be an increasing function satisfying the conditions:

1. $ f(x+1) = f(x) + 1 $ for every $ x \in \mathbb{R} $,

2. there exists an integer $ p $ such that $ f(f(f(0))) = p $. Prove that for every real number $ x $

where $ x_1 = x $ and $ x_n = f(x_{n-1}) $ for $ n = 2, 3, \ldots $. | We will first provide several properties of the function $f$ satisfying condition $1^\circ$ of the problem. Let $f_n(x)$ be the $n$-fold composition of the function $f$, i.e., let $f_1(x) = f(x)$ and $f_{n+1}(x) = f_n(f_1(x))$ for $n = 1, 2, \ldots$. It follows that if $n = k + m$, where $k$ and $m$ are natural numbers, then

We will prove that for any integer $r$, the formula

Consider first the case when $r$ is a natural number. We will use induction. For $r = 1$, formula (2) follows from condition $1^\circ$ of the problem. Assume that for some natural number $r$, formula (2) holds. We will prove the analogous formula for the number $r + 1$. From condition $1^\circ$ and the induction hypothesis, we obtain

Thus, by the principle of induction, formula (2) holds for every natural number $r$.

If $r = 0$, then formula (2) is obviously true. If finally $r = -s$ is a negative integer, then $s$ is a natural number, and therefore

Substituting $y = x - s$ here, we get $f(x) = f(x - s) + s$, i.e., $f(x - s) = f(x) - s$. This is formula (2) for $r = -s$.

By induction with respect to $n$, from formula (2), it follows that for any integer $r$ and natural number $n$,

We now proceed to solve the problem. Notice first that $x_{n+1} = f_n(x)$ for $n = 1, 2, \ldots$, so we need to find the limit of the sequence

$\displaystyle \frac{f_n(x)}{n+1}$. We will first prove that

Let $r$ be the remainder of the division of the natural number $n$ by $3$, i.e., let $n = 3k + r$, where $r = 0, 1$, or $2$ and $k \geq 0$. By induction with respect to $k$, we will prove that

If $k = 0$, then $n = r$ and formula (5) is true. If formula (5) holds for some $k \geq 0$, then the formula for the number $k + 1$ has the form

Formula (6) follows from (1), (3), and (5), since $f_{n+3}(0) = f_n(f_3(0)) = f_n(p) = f_n(0 + p) = f_n(0) + p = kp + f_r(0) + p = (k + 1)p + f_r(0)$.

Thus, by the principle of induction, formula (5) holds for any $k \geq 0$.

Since $k = \displaystyle \frac{n-r}{3} = \frac{n+1}{3} - \frac{1-r}{3}$, it follows from (5) that

Since the expression $(1-r)p + 3f_r(0)$ takes only three values (for $r = 0, 1, 2$), it is bounded. Therefore,

and from (7) it follows that (4).

Now, for any $x \in \mathbb{R}$, let $a = [x]$. Then $a \leq x < a + 1$. Since the function $f$, and therefore $f_n$, is increasing, it follows that

The number $a$ is an integer. Therefore, from (3) and (8), we obtain

Since $\displaystyle \lim_{n \to \infty} \frac{a}{n+1} = 0$, it follows from (4) and (9) by the squeeze theorem that $\displaystyle \lim_{n \to \infty} \frac{f_n(x)}{n+1} = 3$. | 3 | Algebra | proof | Incomplete | Yes | olympiads | false |

XLIV OM - III - Problem 3

Let $ g(k) $ denote the greatest odd divisor of the positive integer $ k $, and let us assume

The sequence $ (x_n) $ is defined by the relations $ x_1 = 1 $, $ x_{n+1} = f(x_n) $. Prove that the number 800 appears exactly once among the terms of this sequence. Determine $ n $ for which $ x_n = 800 $. | Let's list the first fifteen terms of the sequence $ (x_n) $, grouping them into blocks consisting of one, two, three, four, and five terms respectively:

We have obtained five rows of the infinite system (U), which can be continued according to the following rules: the $ j $-th row consists of $ j $ numbers, the last of which is $ 2j - 1 $; each number that is not the last term of any row is twice the number directly above it.

Let's adopt these rules as the definition of the system (U).

Every integer $ k \geq 1 $ can be uniquely represented in the form

and thus appears exactly once in the system (U), specifically at the $ m $-th position in the $ j $-th column (positions in the column are numbered from zero).

If $ k $ is an even number, and thus has the form (1) with $ m \geq 1 $, then $ g(k) = 2j - 1 $, and therefore

This means that $ f(k) $ is in the $ (j + 1) $-th column at the $ (m-1) $-th position, i.e., directly to the right of $ k $.

If $ k $ is an odd number, $ k = 2j - 1 $ (and thus forms the right end of the $ j $-th row), then

In this case, the number $ f(k) $ is the first term of the $ (j + 1) $-th (i.e., the next) row.

Therefore, reading the terms of the table (U) lexicographically, i.e., row by row (and in each row from left to right), we will traverse the consecutive terms of the sequence $ (x_n) $, in accordance with the recursive relationship defining this sequence $ x_{n+1} = f(x_n) $.

Every natural number $ k \geq 1 $ appears in the scheme (U), and thus in the sequence $ x_1, x_2, x_3, \ldots $ exactly once. This applies in particular to the number $ k = 800 $. It remains to locate this number. According to the general rule, the number $ 800 $, equal to $ 2^5(2\cdot 13 -1) $, is in the third column, at the fifth position. Therefore (see formulas (1) and (2)), the number $ f(800) $ is in the fourth column at the fourth position, the number $ f \circ f(800) $ is in the fifth column at the third position, and so on, the number $ f \circ f \circ f \circ f \circ f (800) $ is in the eighth column at the zeroth position, i.e., it forms the right end of the eighteenth row.

Since the $ j $-th row contains $ j $ terms, the number ending the eighteenth row appears in the sequence $ (x_n) $ with the number $ 1 + 2 + 3 + \ldots + 18 = 171 $. If $ 800 = x_N $, then we have the equality $ x_{N+5} = f \circ f \circ f \circ f \circ f (800) = x_{171} $. Therefore (due to the distinctness of the sequence $ (x_n) $), we conclude that $ N + 5 = 171 $, i.e., $ N = 166 $. | 166 | Number Theory | proof | Incomplete | Yes | olympiads | false |

XX OM - II - Task 2

Find all four-digit numbers in which the thousands digit is equal to the hundreds digit, and the tens digit is equal to the units digit, and which are squares of integers. | Suppose the number $ x $ satisfies the conditions of the problem and denote its consecutive digits by the letters $ a, a, b, b $. Then

The number $ x $ is divisible by $ 11 $, so as a square of an integer, it is divisible by $ 11^2 $, i.e., $ x = 11^2 \cdot k^2 $ ($ k $ - an integer), hence

Therefore,

The number $ a+b $ is thus divisible by $ 11 $. Since $ 0 < a \leq 9 $, $ 0 \leq b \leq 9 $, then $ 0 < a+b \leq 18 $, hence

Therefore, we conclude that $ b \ne 0 $, $ b \ne 1 $; since $ b $ is the last digit of the square of an integer, it cannot be any of the digits $ 2, 3, 7, 8 $. Thus, $ b $ is one of the digits $ 4, 5, 6, 9 $. The corresponding values of $ a $ are $ 7, 6, 5, 2 $, so the possible values of $ x $ are only the numbers $ 7744 $, $ 6655 $, $ 5566 $, $ 2299 $. Only the first one is a square of an integer.

The problem has one solution, which is the number $ 7744 $. | 7744 | Number Theory | math-word-problem | Yes | Yes | olympiads | false |

V OM - I - Task 2

Investigate when the sum of the cubes of three consecutive natural numbers is divisible by $18$. | Let $ a - 1 $, $ a $, $ a + 1 $, be three consecutive natural numbers; the sum of their cubes

can be transformed in the following way:

Since one of the numbers $ a - 1 $, $ a $, $ a + 1 $ is divisible by $ 3 $, then one of the numbers $ a $ and $ (a + 1) (a - 1) + 3 $ is also divisible by $ 3 $. Therefore, the sum $ S $ of the cubes of three consecutive natural numbers is always divisible by $ 9 $.

The sum $ S $ is thus divisible by $ 18 = 9 \cdot 2 $ if and only if it is divisible by $ 2 $. Since $ S = 3a^3 + 6a $, $ S $ is even if and only if $ a $ is even, i.e., when $ a - 1 $ is odd. Hence, the conclusion:

The sum of the cubes of three consecutive natural numbers is divisible by $ 18 $ if and only if the first of these numbers is odd. | 3 | Number Theory | math-word-problem | Yes | Yes | olympiads | false |

XXXV OM - II - Task 5

Calculate the lower bound of the areas of convex hexagons, all of whose vertices have integer coordinates. | We will use the following lemma, which was the content of a competition problem in the previous Mathematical Olympiad.

Lemma. Twice the area of a triangle, whose all vertices have integer coordinates, is an integer.

Proof. The area of triangle $ABC$ is equal to half the absolute value of the determinant formed from the coordinates of vectors $\overrightarrow{AB}$ and $\overrightarrow{AC}$. If the coordinates of vertices $A$, $B$, $C$ are integers, then the coordinates of vectors $\overrightarrow{AB}$ and $\overrightarrow{AC}$ are also integers, the determinant formed from these coordinates is also an integer, and consequently, twice the area of triangle $ABC$ is an integer.

Every point on the plane with integer coordinates belongs to exactly one of the following four sets:

$A$ - the set of points whose both coordinates are even,

$B$ - the set of points whose both coordinates are odd,

$C$ - the set of points whose first coordinate is even and the second is odd,

$D$ - the set of points whose first coordinate is odd and the second is even.

When two points on the plane belong to one of these sets, we say they have the same parity type. If points $P = (p_1, p_2)$ and $Q = (q_1, q_2)$ have the same parity type, then the midpoint of segment $\overline{PQ}$ has coordinates $\left( \frac{1}{2} (p_1 + q_1), \frac{1}{2} (p_2 + q_2) \right)$, which are integers (the sum of numbers of the same parity is an even number).

Let's return to convex hexagons whose each vertex has integer coordinates. Among the six vertices of the hexagon, we can find two having the same parity type.

If two consecutive vertices (e.g., $K$ and $L$) of hexagon $KLMNOP$ have the same parity type, then connecting the midpoint $S$ of segment $\overline{KL}$ with point $M$ results in hexagon $KSMNOP$ having a smaller area than hexagon $KLMNOP$. When determining the lower bound of the areas of hexagons, we can therefore limit ourselves to hexagons in which consecutive vertices do not have the same parity type. Therefore, there exist some two non-consecutive vertices having the same parity type. The midpoint of the segment connecting these vertices has integer coordinates and lies inside the hexagon. Connecting this midpoint with all vertices of the hexagon results in six triangles, whose sum of areas equals the area of the hexagon. Therefore, by the lemma, the area of the hexagon is not less than $6 \cdot \frac{1}{2} = 3$. An example of a convex hexagon with vertices having integer coordinates and an area of $3$ is the hexagon with vertices $K = (-1, -1)$, $L = (0, -1)$, $M = (1, 0)$, $N = (1, 1)$, $O = (0, 1)$, $P = (-1, 0)$.

The sought lower bound is therefore $3$. | 3 | Geometry | math-word-problem | Incomplete | Yes | olympiads | false |

LIX OM - II - Task 1

Determine the maximum possible length of a sequence of consecutive integers, each of which can be expressed in the form $ x^3 + 2y^2 $ for some integers $ x, y $. | A sequence of five consecutive integers -1, 0, 1, 2, 3 satisfies the conditions of the problem: indeed, we have

On the other hand, among any six consecutive integers, there exists a number, say

$ m $, which gives a remainder of 4 or 6 when divided by 8. The number $ m $ is even; if there were a representation

in the form $ m = x^3 +2y^2 $ for some integers $ x, y $, then the number $ x $ would be even. In this case, however,

we would obtain the divisibility $ 8|x^3 $ and as a result, the numbers $ m $ and $ 2y^2 $ would give the same remainder (4 or 6) when divided by 8.

Therefore, the number $ y^2 $ would give a remainder of 2 or 3 when divided by 4. This is impossible: the equalities

prove that the square of an integer can give a remainder of only 0 or 1 when divided by 4.

We have thus shown that among any six consecutive integers, there exists a number that cannot be represented

in the form $ x^3 +2y^2 $.

Answer: The maximum possible length of such a sequence is 5. | 5 | Number Theory | math-word-problem | Yes | Yes | olympiads | false |

XV OM - I - Problem 11

In triangle $ ABC $, angle $ A $ is $ 20^\circ $, $ AB = AC $. On sides $ AB $ and $ AC $, points $ D $ and $ E $ are chosen such that $ \measuredangle DCB = 60^\circ $ and $ \measuredangle EBC = 50^\circ $. Calculate the angle $ EDC $. | Let $ \measuredangle EDC = x $ (Fig. 9). Notice that $ \measuredangle ACB = \measuredangle $ABC$ = 80^\circ $, $ \measuredangle CDB = 180^\circ-80^\circ-60^\circ = 40^\circ $, $ \measuredangle CEB = 180^\circ - 80^\circ-50^\circ = \measuredangle EBC $, hence $ EC = CB $. The ratio $ \frac{DC}{CE} $ of the sides of triangle $ EDC $ equals the ratio of the sides $ \frac{DC}{CB} $ of triangle $ BDC $, so the ratios of the sines of the angles opposite the corresponding sides in these triangles are equal:

The right side of the obtained equation can be transformed:

We need to find the convex angle $ x $ that satisfies the equation

or the equation

By transforming the products of sines into differences of cosines, we obtain an equivalent equation

Considering the condition $ 0 < x < 180^\circ $, we get $ x = 30^\circ $.

Note. The last part of the solution can be slightly shortened. Specifically, from the form of equation (1), it is immediately clear that it has a root $ x = 30^\circ $. No other convex angle satisfies this equation; if

then

so

thus, if $ 0 < x < 180^\circ $ and $ 0 < y < 180^\circ $, then $ x = y $. | 30 | Geometry | math-word-problem | Yes | Yes | olympiads | false |

Given an integer $ n \geq 5 $. Determine the number of solutions in real numbers $ x_1, x_2, x_3, \ldots, x_n $ of the system of equations

where $ x_{-1}=x_{n-1}, $ $ x_{0}=x_{n}, $ $ x_{1}=x_{n+1}, $ $ x_{2}=x_{n+2} $. | Adding equations side by side, we obtain

Thus, the numbers $ x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_n $ take values 0 or 1. The task reduces to finding the number of solutions to the system of equations

in numbers belonging to the set $ \{0,1\} $.

Notice that the system of equations (1) is satisfied when $ x_i = x_2 = \dots = x_n = 1 $ or when $ x_1 = x_2 = \ldots = x_n = 0 $.

Assume that the number $ n $ is not divisible by 3. Then we obtain

from which $ x_n = x_2 $. Similarly, we prove that $ x_i = x_{i+2} $ for $ i = 1,2,\ldots,n-1 $. Therefore, if $ n $ is an odd number not divisible by 3, the only solutions $ (x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_n) $ to the system (1) are $ (0,0,0,\ldots,0) $ and $ (1,1,1,\ldots, 1) $. For even numbers $ n $ not divisible by 3, we obtain two additional solutions $ (x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_n) $, namely

Now assume that the number $ n $ is divisible by 3. Then the system of equations (1) has at least 8 solutions: the unknowns can repeat periodically with a period of 3.

Let's examine the existence of solutions $ (x_1, x_2, x_3, \ldots, x_n) $ that are not periodic with a period of 3. Without loss of generality, assume that $ x_1 = x_4 $. Then the equality $ x_1 + x_2 = x_4 + x_5 $ is possible only if $ x_1 + x_2 = 1 $. Hence, $ x_1 = x_2 $ and $ x_2 = x_5 $.

Repeating the reasoning, we find that $ x_2 = x_3 $ and $ x_3 = x_6 $, so for any $ i $ we have $ x_i = x_{i+1} $. Therefore, the unknowns must alternate between 0 and 1, which is possible only for even $ n $.

In summary: the number of solutions to the given system of equations is:

2 for $ n $ relatively prime to 6;

4 for even $ n $ not divisible by 3;

8 for odd $ n $ divisible by 3;

10 for $ n $ divisible by 6. | 2 | Algebra | math-word-problem | Incomplete | Yes | olympiads | false |

XXVIII - II - Task 3

In a hat, there are 7 slips of paper. On the $ n $-th slip, the number $ 2^n-1 $ is written ($ n = 1, 2, \ldots, 7 $). We draw slips randomly until the sum exceeds 124. What is the most likely value of this sum? | The sum of the numbers $2^0, 2^1, \ldots, 2^6$ is $127$. The sum of any five of these numbers does not exceed $2^2 + 2^3 + 2^4 + 2^5 + 2^6 = 124$. Therefore, we must draw at least six slips from the hat.

Each of the events where we draw six slips from the hat, and the seventh slip with the number $2^{n-1}$ ($n = 1, 2, \ldots, 7$) remains in the hat, is equally likely. The probability of such an event is thus $\displaystyle \frac{1}{7}$.

The sum of the numbers on the drawn slips is equal to $127 - 2^{n-1}$. If $n = 1$, this sum is $126$; if $n = 2$, it is $125$; if $n = 3, 4, 5, 6$ or $7$, the sum is less than $124$ and we must draw a seventh slip. In this last case, the sum of the numbers on all the drawn slips will be $127$. Therefore, the probability that the sum of the numbers on all the slips drawn according to the conditions of the problem is $125$, $126$, or $127$, is $\displaystyle \frac{1}{7}$, $\displaystyle \frac{1}{7}$, $\displaystyle \frac{5}{7}$, respectively.

Thus, the most probable value of the sum is $127$. | 127 | Number Theory | math-word-problem | Yes | Yes | olympiads | false |

XLII OM - I - Problem 8

Determine the largest natural number $ n $ for which there exist in space $ n+1 $ polyhedra $ W_0, W_1, \ldots, W_n $ with the following properties:

(1) $ W_0 $ is a convex polyhedron with a center of symmetry,

(2) each of the polyhedra $ W_i $ ($ i = 1,\ldots, n $) is obtained from $ W_0 $ by a translation,

(3) each of the polyhedra $ W_i $ ($ i = 1,\ldots, n $) has a point in common with $ W_0 $,

(4) the polyhedra $ W_0, W_1, \ldots, W_n $ have pairwise disjoint interiors. | Suppose that polyhedra $W_0, W_1, \ldots, W_n$ satisfy the given conditions. Polyhedron $W_1$ is the image of $W_0$ under a translation by a certain vector $\overrightarrow{\mathbf{v}}$ (condition (2)). Let $O_0$ be the center of symmetry of polyhedron $W_0$ (condition (1)); the point $O_1$, which is the image of $O_0$ under the translation by $\overrightarrow{\mathbf{v}}$, is the center of symmetry of $W_1$. Figure 3 illustrates a planar variant of the considered problem (a representation of the spatial configuration would obscure this illustration); polyhedra $W_0$ and $W_1$ are depicted as centrally symmetric polygons.

om42_1r_img_3.jpg

By condition (3), polyhedra $W_0$ and $W_1$ have common points (possibly many). Let $K$ be a common point of $W_0$ and $W_1$ (arbitrarily chosen). Denote by $L$ the image of point $K$ under the central symmetry with respect to $O_1$; thus, $L \in W_1$. Let $N$ be a point such that $\overrightarrow{NL} = \overrightarrow{\mathbf{v}}$ and let $M$ be the midpoint of segment $NK$ (Figure 4). Therefore, $N \in W_0$. According to condition (1), the set $W_0$ is convex; this means that with any two points belonging to $W_0$, the entire segment connecting these points is contained in $W_0$. Since $K \in W_0$ and $N \in W_0$, it follows that $M \in W_0$. Segment $MO_1$ connects the midpoints of segments $KN$ and $KL$, and thus $\overrightarrow{MO_1} = \frac{1}{2} \overrightarrow{NL} = \frac{1}{2} \overrightarrow{\mathbf{v}}$, which means $M$ is the midpoint of segment $O_0O_1$.

Let $U$ be the image of polyhedron $W_0$ under a homothety with center $O_0$ and scale factor 3. We will show that $W_1 \subset U$. Take any point $P \in W_1$: let $Q \in W_0$ be a point such that $\overrightarrow{QP} = \overrightarrow{\mathbf{v}}$ and let $S$ be the center of symmetry of parallelogram $O_0O_1PQ$. The medians $O_0S$ and $QM$ of triangle $O_0O_1Q$ intersect at a point $G$ such that $\overrightarrow{O_0G} = \frac{2}{3}\overrightarrow{O_0S} = \frac{1}{3}\overrightarrow{O_0P}$ (Figure 5). This means that $P$ is the image of point $G$ under the considered homothety. Since $G$ is a point on segment $QM$ with endpoints in the set (convex) $W_0$, it follows that $G \in W_0$. Therefore, $P \in U$ and from the arbitrariness of the choice of point $P \in W_1$ we conclude that $W_1 \subset U$.

om42_1r_img_4.jpg

om42_1r_img_5.jpg

In the same way, we prove that each of the sets $W_i (i=1, \ldots, n)$ is contained in $U$. Of course, also $W_0 \subset U$. Thus, the set $W_0 \cup W_1 \cup \ldots \cup W_n$ is a polyhedron contained in $U$. By conditions (2) and (4), its volume equals the volume of $W_0$ multiplied by $n+1$. On the other hand, the volume of $U$ equals the volume of $W_0$ multiplied by 27. Therefore, $n \leq 26$.

It remains to note that the value $n = 26$ can be achieved (example realization: 27 cubes $W_0, \ldots, W_{26}$ arranged like a Rubik's cube). Thus, the sought number is $26$.

Note. We obtain the same result assuming that $W_0, \ldots, W_n$ are any bounded, closed convex bodies (not necessarily polyhedra), with non-empty interiors, satisfying conditions (1)-(4); the reasoning carries over without any changes. Moreover, condition (4) turns out to be unnecessary. This was proven by Marcin Kasperski in the work 27 convex sets without a center of symmetry, awarded a gold medal at the Student Mathematical Paper Competition in 1991; a summary of the work is presented in Delta, issue 3 (1992). | 26 | Geometry | math-word-problem | Yes | Yes | olympiads | false |

XXIV OM - III - Task 2

Let $ p_n $ be the probability that a series of 100 consecutive heads will appear in $ n $ coin tosses. Prove that the sequence of numbers $ p_n $ is convergent and calculate its limit. | The number of elementary events is equal to the number of $n$-element sequences with two values: heads and tails, i.e., the number $2^n$. A favorable event is a sequence containing 100 consecutive heads. We estimate the number of unfavorable events from above, i.e., the number of sequences not containing 100 consecutive heads.

Let $n = 100k + r$, where $k \geq 0$ and $0 \leq r < 100$. Each $n$-element sequence thus consists of $k$ 100-element sequences and one $r$-element sequence. The total number of 100-element sequences with two values is $2^{100}$; therefore, after excluding the sequence composed of 100 heads, there remain $2^{100} - 1$ 100-element sequences. Each $n$-element sequence not containing 100 consecutive heads thus consists of $k$ such 100-element sequences and some $r$-element sequence. Hence, the number of unfavorable events is not greater than $(2^{100} - 1)^k \cdot 2^r$. Therefore,

If $n$ tends to infinity, then of course $k$ also tends to infinity. Since for $0 < q < 1$ we have $\displaystyle \lim_{k \to \infty} q^k = 0$, then $\displaystyle \lim_{k \to \infty} \left( 1 - \frac{1}{2^{100}} \right)^k = 0$. Therefore, from (1) by the squeeze theorem, we have $\displaystyle \lim_{k \to \infty} q^k = 0$, so $\displaystyle \lim_{n \to \infty} p_n = 1$. | 1 | Combinatorics | proof | Yes | Yes | olympiads | false |

XXVIII - I - Problem 11

From the numbers $ 1, 2, \ldots, n $, we choose one, with each of them being equally likely. Let $ p_n $ be the probability of the event that in the decimal representation of the chosen number, all digits: $ 0, 1, \ldots, 9 $ appear. Calculate $ \lim_{n\to \infty} p_n $. | Let the number $ n $ have $ k $ digits in its decimal representation, i.e., let $ 10^{k-1} \leq n < 10^k $, where $ k $ is some natural number. Then each of the numbers $ 1, 2, \ldots, n $ has no more than $ k $ digits. We estimate from above the number $ A_0 $ of such numbers with at most $ k $ digits that do not contain the digit $ 0 $ in their decimal representation.

The number of $ r $-digit numbers whose decimal representation does not contain the digit $ 0 $ is equal to $ 9^r $, because each of the $ r $ digits of such a number belongs to the nine-element set $ \{1, 2, \ldots, 9\} $. Therefore,

Similarly, we observe that for $ i = 1, 2, \ldots, 9 $ the number $ A_i $ of numbers with at most $ k $ digits that do not contain the digit $ i $ in their decimal representation satisfies the inequality $ A_i < 9^{k+1} $.

It follows that the number $ A $ of natural numbers among $ 1, 2, \ldots, n $ that do not contain at least one of the digits $ 0, 1, 2, \ldots, 9 $ in their decimal representation satisfies the inequality

Therefore, the number $ B_n $ of numbers among $ 1, 2, \ldots, n $ whose decimal representation contains all the digits $ 0, 1, 2, \ldots, 9 $ satisfies

Thus,

If $ n $ tends to infinity, then $ k $ also tends to infinity. Since for any number $ q $ in the interval $ (-1; 1) $ we have $ \displaystyle \lim_{k \to \infty} q^k = 0 $, in particular $ \displaystyle \lim_{k \to \infty} \left( \frac{9}{10} \right)^k = 0 $. Therefore, from (1) by the squeeze theorem, it follows that $ \lim_{n \to \infty} p_n = 1 $. | 0 | Combinatorics | math-word-problem | Yes | Incomplete | olympiads | false |

XXII OM - III - Problem 5

Find the largest integer $ A $ such that for every permutation of the set of natural numbers not greater than 100, the sum of some 10 consecutive terms is at least $ A $. | The sum of all natural numbers not greater than $100$ is equal to $1 + 2 + \ldots + 100 = \frac{1 + 100}{2} \cdot 100 = 5050$. If $a_1, a_2, \ldots, a_{100}$ is some permutation of the set of natural numbers not greater than $100$ and the sum of any $10$ terms of this permutation is less than some number $B$, then in particular

By adding these inequalities side by side, we get that $a_1 + a_2 + \ldots + a_{100} = 1 + 2 + \ldots + 100 < 10B$, which means $505 < B$.

Thus, the number $A$ defined in the problem satisfies the inequality

On the other hand, consider the following permutation $a_1, a_2, \ldots, a_{100}$ of the set of natural numbers not greater than $100$

This permutation can be defined by the formulas:

We will prove that the sum of any $10$ consecutive terms of this permutation is not greater than $505$.

Indeed, if the first of the considered $10$ terms has an even number $2k$, then

If, however, the first of the considered terms has an odd number $2k + 1$, then

Thus, the sum of any $10$ consecutive terms of this permutation is not greater than $505$. Therefore, the number $A$ defined in the problem satisfies the inequality

From (1) and (2), it follows that $A = 505$.

Note 1. The problem can be generalized as follows: Find the largest integer $A$ such that for any permutation of the set of natural numbers not greater than an even number $n = 2t$, the sum of some $m = 2r$ (where $r$ is a divisor of $t$) consecutive terms is at least $A$.

By making minor changes in the solution provided above, consisting in replacing the number $100$ with $2t$ and the number $10$ with $2r$, it can be proved that $A = \frac{1}{2} m(n + 1)$.

Note 2. In the case where $m \leq n$ are any natural numbers, it is generally not true that every permutation of the set of natural numbers not greater than $n$ contains $m$ consecutive terms with a sum not less than $\frac{1}{2} m(n + 1)$. For example, for $n = 6$, $m = 4$, the permutation $6, 4, 1, 2, 3, 5$ does not contain four consecutive terms with a sum not less than $14$. | 505 | Combinatorics | math-word-problem | Yes | Yes | olympiads | false |

XV OM - II - Task 3

Prove that if three prime numbers form an arithmetic progression with a difference not divisible by 6, then the smallest of these numbers is $3$. | Suppose that the prime numbers $ p_1 $, $ p_2 $, $ p_3 $ form an arithmetic progression with a difference $ r > 0 $ not divisible by $ 6 $, and the smallest of them is $ p_1 $. Then

Therefore, $ p_1 \geq 3 $, for if $ p_1 = 2 $, the number $ p_3 $ would be an even number greater than $ 2 $, and thus would not be a prime number. Hence, the numbers $ p_1 $ and $ p_2 $ are odd, and the number $ r $ equal to the difference $ p_2 - p_1 $ is even and one of the cases holds: $ r = 6k + 2 $ or $ r = 6k + 4 $, where $ k $ is an integer $ \geq 0 $.

We will prove that $ p_1 $ is divisible by $ 3 $. Indeed, if $ p_1 = 3m + 1 $ ($ m $ - an integer) and $ r = 6k + 2 $, it would follow that $ p_2 = 3m + 6k + 3 $ is divisible by $ 3 $, and since $ p_2 > 3 $, $ p_2 $ would not be a prime number. If, on the other hand, $ p_1 = 3m + 1 $ and $ r = 6k + 4 $, then $ p_3 = 3m + 12k + 9 $ would not be a prime number. Similarly, from the assumption that $ p_1 = 3m + 2 $ and $ r = 6k + 2 $, it would follow that $ p_3 = 3m + 12k + 6 $ is not a prime number, and from the assumption that $ p_1 = 3m + 2 $ and $ r = 6k + 4 $, we would get $ p_2 = 3m + 6k + 6 $, and thus $ p_2 $ would not be a prime number.

Therefore, $ p_1 $ is a prime number divisible by $ 3 $, i.e., $ p_1 = 3 $. | 3 | Number Theory | proof | Yes | Yes | olympiads | false |

LII OM - III - Task 4

Given such integers $ a $ and $ b $ that for every non-negative integer $ n $ the number $ 2^na + b $ is a square of an integer. Prove that $ a = 0 $.

| If $ b = 0 $, then $ a = 0 $, because for $ a \ne 0 $, the numbers $ a $ and $ 2a $ cannot both be squares of integers.

If the number $ a $ were negative, then for some large natural number $ n $, the number $ 2^n a + b $ would also be negative, and thus could not be a square of an integer.

The only case left to consider is when $ a \geq 0 $ and $ b \neq 0 $.

For every positive integer $ k $, the numbers

are squares of different non-negative integers, say

Then $ x_{k}+y_{k}\leq(x_{k}+y_{k})|x_{k}-y_{k}|=|x_{k}^{2}-y_{k}^{2}|=|3b| $, hence

Thus the sequence $ (x_k) $ is bounded, which is only possible if $ a = 0 $. | 0 | Number Theory | proof | Yes | Incomplete | olympiads | false |

XLIII OM - I - Problem 2

In square $ABCD$ with side length $1$, point $E$ lies on side $BC$, point $F$ lies on side $CD$, the measures of angles $EAB$ and $EAF$ are $20^{\circ}$ and $45^{\circ}$, respectively. Calculate the height of triangle $AEF$ drawn from vertex $A$. | The measure of angle $ FAD $ is $ 90^\circ - (20^\circ + 45^\circ) = 25^\circ $. From point $ A $, we draw a ray forming angles of $ 20^\circ $ and $ 25^\circ $ with rays $ AE $ and $ AF $, respectively, and we place a segment $ AG $ of length $ 1 $ on it (figure 2).

From the equality $ |AG| =|AB| = 1 $, $ | \measuredangle EAG| = | \measuredangle EAB| = 20^\circ $, it follows that triangle $ EAG $ is congruent to $ EAB $.

Similarly, from the equality $ |AG| = |AD| = 1 $, $ | \measuredangle FAG| = | \measuredangle FAD| = 25^\circ $, it follows that triangle $ FAG $ is congruent to $ FAD $.

This means that

point $ G $ lies on segment $ EF $ and is the foot of the altitude of triangle $ AEF $ drawn from vertex $ A $. Its length $ |AG| = 1 $. | 1 | Geometry | math-word-problem | Yes | Yes | olympiads | false |

XIV OM - I - Task 5

How many digits does the number

have when written in the decimal system? | The task can be easily solved using 5-digit decimal logarithm tables. According to the tables, $\log 2$ is approximately $0.30103$, with the error of this approximation being less than $0.00001$, hence

therefore

after multiplying by $2^{16} = 65536$, we obtain the inequality

From this, it follows that the number $2^{2^{16}}$ has $19728$ or $19729$ digits, which does not yet provide an answer to the question. To obtain it, we need to estimate $\log 2$ more accurately. For this purpose, we will use the approximate value of the logarithm of the number $2^{10} = 1024$ given in the tables. According to the tables, $\log 1024 \approx 3.01030$ with an error less than $0.00001$, hence

therefore

so

Thus, the number $2^{2^{16}}$ has $19729$ digits. Since the number $2^{2^{16}}$ is even, its last digit is not $9$, hence the number $2^{2^{16}} + 1$ also has $19729$ digits. | 19729 | Number Theory | math-word-problem | Incomplete | Yes | olympiads | false |

XLIV OM - I - Problem 6

The sequence $ (x_n) $ is defined as follows:

Calculate the sum $ \sum_{n=0}^{1992} 2^n x_n $. | Let's replace the parameter $1992$ with any arbitrarily chosen natural number $N \geq 1$ and consider the sequence $(x_n)$ defined by the formulas

when $N = 1992$, this is the sequence given in the problem.

Let's experiment a bit. If $N = 3$, the initial terms of the sequence $(x_n)$ are the numbers $3$, $-9$, $9$, $-3$. If $N = 4$, the initial terms of the sequence $(x_n)$ are the numbers $4$, $-16$, $24$, $-16$, $4$. If $N = 5$, the initial terms of the sequence $(x_n)$ are the numbers $5$, $-25$, $50$, $-50$, $25$, $-5$. These observations lead to the conjecture that for every natural number $N \geq 1$, the equality

holds.

To prove this, we will use the auxiliary equality

which holds for any natural numbers $N \geq n \geq 1$. Here is its justification:

We treat $N$ as fixed. For $n = 1$, formula (2) holds. Assume that formula (2) is true for some $n$ ($1 \leq n \leq N-1$). We will use the basic property of binomial coefficients:

Multiplying both sides of this equality by $(-1)^n$ and adding to the corresponding sides of equality (2):

more concisely:

This is equality (2) with $n$ replaced by $n+1$. By the principle of induction, formula (2) holds for $n = 1, 2, \ldots, N$.

We proceed to the proof of formula (1). For $n = 0$, the formula holds. Take any natural number $n$ (satisfying the conditions $1 \leq n \leq N$) and assume inductively that the equality $x_k = (-1)^k N \binom{N}{k}$ (i.e., (1) with $n$ replaced by $k$) holds for $k = 0, 1, \ldots, n-1$. We transform the expression defining $x_n$, using formula (2):

We have shown the validity of formula (1) for the chosen number $n$. Therefore, by induction, we conclude that equality (1) holds for all $n \in \{1, 2, \ldots, N\}$.

Thus,

The sum appearing in the last expression is the expansion (by Newton) of the $N$-th power of the binomial $(-2 + 1)$. Therefore,

This is the desired value. For $N = 1992$, it is $1992$. | 1992 | Algebra | math-word-problem | Incomplete | Yes | olympiads | false |

XLVIII OM - I - Problem 8

Let $ a_n $ be the number of all non-empty subsets of the set $ \{1,2,\ldots,6n\} $, the sum of whose elements gives a remainder of 5 when divided by 6, and let $ b_n $ be the number of all non-empty subsets of the set $ \{1,2,\ldots,7n\} $, the product of whose elements gives a remainder of 5 when divided by 7. Calculate the quotient $ a_n/b_n $. | For a finite set of numbers $A$, the symbols $s(A)$ and $p(A)$ will denote the sum and the product of all numbers in this set, respectively. Let $n$ be a fixed natural number. According to the problem statement,

Notice that in the definition of the number $b_n$, we can remove all multiples of the number $7$ from the set $\{1,2,\ldots,7n\}$; if a set $B$ contains any number divisible by $7$, then the condition $p(B) \equiv 5 (\mathrm{mod} 7)$ is certainly not satisfied. By adopting the notation

and

we can thus rewrite the definitions of the numbers $a_n$ and $b_n$ as follows:

Consider any number $x \in X$. It is an element of exactly one of the sets $X_0, X_1, \ldots, X_{n-1}$. The number $3^x$ is not divisible by $7$, so in each of the sets $Y_0, Y_1, \ldots, Y_{n-1}$ there is exactly one element congruent to $3^x$ modulo $7$. Among them, we choose the element $y$ belonging to the set $Y_k$ with the same index $k$ as the index of the set $X_k$ containing $x$. Denote this element $y$ by $h(x)$. In this way, a function $h: X \to Y$ is defined with the property:

We will show that this function is injective.

Suppose that $h(u) = h(v)$ for some numbers $u, v \in X$. Assume that $u \leq v$ and $u \in X_k$, $v \in X_l$. Then $h(u) \in Y_k$, $h(v) \in Y_l$, so from the equality $h(u) = h(v)$ it follows that $k = l$, and moreover,

The key to further considerations is the following, easy to verify, property:

Since $u \leq v$ and $u, v \in X_k$, we have $0 \leq v - u \leq 5$. Multiplying the relation (3) by the integer $3^{6(k+1)-u}$ on both sides, we get

From this, using formulas (4), we first infer that $1 \equiv 3^{v-u} (\mathrm{mod} 7)$, and then that $v - u = 0$, i.e., $u = v$. The injectivity of the function $h$ has been established.

The function $h$ maps the set $X$, which has $6n$ elements, to the set $Y$, which also has $6n$ elements. Hence, it follows that it is a bijective mapping from the set $X$ onto the entire set $Y$.

Now let $A$ be any non-empty subset of the set $X$ and let $h(A)$ be the image of the set $A$ under the mapping $h$. We will prove that the implication holds:

Assume that $A = \{x_1, \ldots, x_m\}$. Then $h(A) = \{y_1, \ldots, y_m\}$, where

(see (2)). If $s(A) \equiv r (\mathrm{mod} 6)$, $0 \leq r < 6$, then there exists an integer $q \geq 0$ such that $x_1 + \ldots + x_m = 6q + r$. Using the first formula (4) again, we calculate:

This proves the validity of the implication (5).

Using property (4), it is not difficult to verify that $3^5 \equiv 5 (\mathrm{mod} 7)$ and $3^r \not\equiv 5 (\mathrm{mod} 7)$ for $r \neq 5 \ (0 \leq r < 6)$. From statement (5), it follows that

And since $h$ is a bijective mapping from the set $X$ to $Y$, we conclude from this that there are as many subsets $A$ of the set $X$ that satisfy the condition $s(A) \equiv 5 (\mathrm{mod} 6)$ as there are subsets $B$ of the set $Y$ that satisfy the condition $p(B) \equiv 5 (\mathrm{mod} 7)$. This means that $a_n = b_n$.

We obtain the answer: for every natural number $n$, the quotient $a_n / b_n$ is equal to $1$.

Note: Property (5) can be expressed in words—suggestively, though not strictly: the mapping $h$ "translates" addition modulo $6$ into multiplication modulo $7$. Readers familiar with the simplest facts and language of group theory know that the set $\{0, \ldots, 5\}$ is a group under the operation of addition modulo $6$, and the set $\{1, \ldots, 6\}$ is a group under the operation of multiplication modulo $7$.

The mentioned property, already in precise terminology, states that the operation which assigns to a number $x \in \{0, \ldots, 5\}$ the remainder of the division of $3^x$ by $7$ is an *isomorphism* of the first of these groups onto the second one—and this observation underlies the entire solution above.

A crucial role is played by the fact that the powers of three $3^0, 3^1, \ldots, 3^5$ give different remainders when divided by $7$—see formulas (4). The same property holds for five; therefore, one can consistently replace exponentiation with base $3$ with exponentiation with base $5$ everywhere, and the modified solution will also be correct. | 1 | Combinatorics | math-word-problem | Yes | Incomplete | olympiads | false |

LI OM - I - Task 10

In space, there are three mutually perpendicular unit vectors $ \overrightarrow{OA} $, $ \overrightarrow{OB} $, $ \overrightarrow{OC} $. Let $ \omega $ be a plane passing through the point $ O $, and let $ A', $ B', $ C' $ be the projections of points $ A $, $ B $, $ C $ onto the plane $ \omega $, respectively. Determine the set of values of the expression

for all planes $ \omega $.

| We will show that the value of expression (1) is equal to $ 2 $, regardless of the choice of plane $ \omega $.

Let $ \omega $ be any plane passing through point $ O $, and $ \pi $ be a plane containing points $ O $, $ A $, $ B $. Denote by $ \ell $ the common line of planes $ \pi $ and $ \omega $. Let $ X $, $ Y $ be the orthogonal projections of points $ A $, $ B $ onto the line $ \ell $. Then, regardless of the position of points $ A $, $ B $ relative to the line $ \ell $ (Fig. 1 and 2),

om51_1r_img_10.jpg

om51_1r_img_11.jpg

Hence

Moreover, $ \measuredangle AXA = (\text{angle between planes } \pi \text{ and } \omega) = \beta $. Therefore, by equality (2),

By the Pythagorean theorem and the above equality, we obtain

The vector $ \overrightarrow{OC} $ is perpendicular to the plane $ \pi $, so $ \measuredangle COC. Therefore,

Adding the equations (3) and (4) side by side, we get

regardless of the choice of plane $ \omega $. | 2 | Geometry | math-word-problem | Incomplete | Yes | olympiads | false |

L OM - I - Problem 11

In an urn, there are two balls: a white one and a black one. Additionally, we have 50 white balls and 50 black balls at our disposal. We perform the following action 50 times: we draw a ball from the urn, and then return it to the urn along with one more ball of the same color as the drawn ball. After completing these actions, we have 52 balls in the urn. What is the most probable number of white balls in the urn? | Let $ P(k,n) $, where $ 1 \leq k\leq n-1 $, denote the probability of the event that when there are $ n $ balls in the urn, exactly $ k $ of them are white. Then

Using the above relationships, we prove by induction (with respect to $ n $) that $ P(k,n) = 1/(n-1) $ for $ k = 1,2,\ldots,n-1 $. In particular

Therefore, each possible number of white balls after $ 50 $ draws (from $ 1 $ to $ 51 $) is equally likely. | 51 | Combinatorics | math-word-problem | Yes | Yes | olympiads | false |

LII OM - I - Task 1

Solve in integers the equation

| We reduce the given equation to the form $ f (x) = f (2000) $, where

Since $ f $ is an increasing function on the interval $ \langle 1,\infty ) $, the given equation has only one solution in this interval, which is $ x = 2000 $. On the set $ (-\infty,0\rangle $, the function $ f $ is decreasing, so there is at most one negative integer $ a $ for which $ f (a) = f (2000) $. However,

and

Therefore, $ a \in (-2000,-1999) $, which contradicts the fact that $ a $ is an integer.

Answer: The given equation has one integer solution: $ x = 2000 $. | 2000 | Number Theory | math-word-problem | Incomplete | Yes | olympiads | false |

XLVI OM - III - Problem 2

The diagonals of a convex pentagon divide this pentagon into a pentagon and ten triangles. What is the maximum possible number of triangles with equal areas? | om46_3r_img_12.jpg

Let's denote the considered pentagon by $ABCDE$, and the pentagon formed by the intersection points of the diagonals by $KLMNP$ so that the following triangles are those mentioned in the problem:

$\Delta_0$: triangle $LEM$; $\quad \Delta_1$: triangle $EMA$;

$\Delta_2$: triangle $MAN$; $\quad \Delta_3$: triangle $ANB$;

$\Delta_4$: triangle $NBP$; $\quad \Delta_5$: triangle $BPC$;

$\Delta_6$: triangle $PCK$; $\quad \Delta_7$: triangle $CKD$;

$\Delta_8$: triangle $KDL$; $\quad \Delta_9$: triangle $DLE$

(figure 12). We will start by proving the implication:

We assume that the numbering of the triangles is cyclic (that is, we assume: $\Delta_{-1} = \Delta_9$; $\Delta_{10} = \Delta_0$).

Suppose, for example, that triangles $\Delta_4$, $\Delta_5$, and $\Delta_6$ have equal areas. From the equality of the areas of triangles $NBP$ and $BPC$, it follows that segment $BP$ is a median in triangle $BCN$; from the equality of the areas of triangles $BPC$ and $PCK$, it follows that segment $CP$ is a median in triangle $BCK$. Point $P$ would then be the common midpoint of diagonals $BK$ and $CN$ of quadrilateral $BCKN$, which should therefore be a parallelogram - but the lines $BN$ and $CK$ intersect at point $E$. This is a contradiction; implication (1) is proven.

We proceed to the main solution. The example of a regular pentagon shows that it is possible to obtain five triangles $\Delta_i$ with equal areas. We will prove that it is not possible to obtain seven such triangles.

Suppose, therefore, that there exists a seven-element set $Z$, contained in the set $\{0,1,\ldots,9\}$, such that triangles $\Delta_i$ with indices $i \in Z$ have equal areas. Let $k$, $l$, $m$ be three numbers from the set $\{0,1,\ldots,9\}$, not belonging to $Z$. Consider all triples of consecutive indices:

where, as before, the addition $i \pm 1$ should be understood modulo $10$. Each number from the set $\{0,1,\ldots,9\}$ belongs to exactly three triples $T_i$. This applies, in particular, to each of the numbers $k$, $l$, $m$. Therefore, the three-element set $\{k,l,m\}$ has a non-empty intersection with at most nine triples $T_i$. At least one triple $T_j$ remains that does not contain any of the numbers $k$, $l$, $m$, and is therefore contained in the set $Z$. The number $j$ must be even, according to observation (1).

Without loss of generality, assume that $j = 2$. This means that the numbers $1$, $2$, $3$ belong to the set $Z$. Therefore, the numbers $0$ and $4$ cannot belong to it (since, again by observation (1), the triples $\{0,1,2\}$ and $\{2,3,4\}$ are excluded); thus, one of the numbers $k$, $l$, $m$ equals $0$, and another equals $4$. The third of these numbers must be part of the triple $\{6,7,8\}$ (which otherwise would be contained in the set $Z$, contrary to implication (1)). The roles of the numbers $6$ and $8$ are symmetric in this context. We therefore have to consider two essentially different cases:

The set $Z$, respectively, has one of the following forms:

Let $S_i$ be the area of triangle $\Delta_i$ (for $i = 0,1,\ldots,9$). We will show that the implications hold:

This will be a proof that none of the seven-element sets $Z$ listed above can be the set of indices of triangles with equal areas. According to earlier statements, this will also justify the conclusion that among the ten triangles $\Delta_i$, there are never seven triangles with the same area.

Proof of implication (2). From the given equalities of areas:

and

it follows (respectively) that points $N$ and $P$ are the midpoints of segments $BM$ and $BK$, and points $M$ and $L$ are the midpoints of segments $EN$ and $EK$ (figure 13).

Thus, segment $NP$ connects the midpoints of two sides of triangle $BMK$, and segment $ML$ connects the midpoints of two sides of triangle $ENK$, and therefore

- and

The obtained parallelism relations show that quadrilateral $AMKN$ is a parallelogram; hence $|MK| = |AN|$. Line $MK$ is parallel to $NC$, so triangles $ENC$ and $EMK$ are similar in the ratio $|EN| : |EM| = 2$. Therefore, $|NC| = 2 \cdot |MK|$, and consequently

The segments $PC$ and $AN$, lying on the same line, are the bases of triangles $ANB$ and $BPC$ with a common vertex $B$. The ratio of the lengths of these bases is therefore also the ratio of the areas of the triangles: area($BPC$) : area($ANB$) = $3 : 2$, i.e., $S_5 : S_3 = 3 : 2$. The conclusion of implication (2) is thus proven.

om46_3r_img_13.jpg

om46_3r_img_14.jpg

Proof of implication (3). The given equalities of the areas of triangles:

and

show that points $M$ and $N$ divide segment $EB$ into three equal parts, and similarly, points $L$ and $K$ divide segment $EC$ into three equal parts. Therefore, line $BC$ is parallel to $ML$ (i.e., to $AM$). Since $N$ is the midpoint of segment $BM$, triangles $AMN$ and $CBN$ are similar in the ratio $-1$ (figure 14). Hence, area($AMN$) = area($CBN$) $> $ area($CBP$), i.e., $S_2 > S_5$. This completes the proof of implication (3), and thus also the proof of the general theorem: it is not possible to have seven triangles $\Delta_i$ with equal areas.

The reasoning conducted in the last case (proof of (3)) also provides a hint on how to obtain six triangles $\Delta_i$ with equal areas. We take any isosceles triangle $BCE$ where $|EB| = |EC|$. On the sides $EB$ and $EC$, we find points $M$ and $N$ and $L$ and $K$, dividing these sides into three equal parts:

The intersection points of line $ML$ with lines $CN$ and $BK$ are denoted by $A$ and $D$, respectively (figure 14 can still serve as an illustration; one only needs to imagine moving point $E$ to the perpendicular bisector of side $BC$ and appropriately repositioning the other points). The equalities (4) and (5) then hold; and thanks to the assumption that triangle $BCE$ is isosceles (and the resulting symmetry of the entire configuration), all areas appearing in relations (4) and (5) are equal.

Conclusion: six of the triangles $\Delta_i$ can have equal areas, and this number cannot be increased. | 6 | Geometry | math-word-problem | Yes | Yes | olympiads | false |

XXII OM - I - Problem 4

Determine the angles that a plane passing through the midpoints of three skew edges of a cube makes with the faces of the cube. | Let $P$, $Q$, $R$ be the midpoints of three skew edges of a cube with edge length $a$ (Fig. 7). Let $n$ be the plane of triangle $PQR$, and $\pi$ be the plane of the base $ABCD$.

Triangle $PQR$ is equilateral because by rotating the cube $90^\circ$ around a vertical axis (passing through the centers of faces $ABCD$ and $A$), and then around a horizontal axis (passing through the centers of faces $ADD$ and $BCC$), points $P$, $O$, $R$ will respectively move to $Q$, $R$, $P$. Therefore, $PQ = QR = RP$.

Let $E$ be the midpoint of segment $RQ$. Then point $E$ is equidistant from faces $ABCD$ and $A$, and thus line $PE$ is parallel to plane $\pi$, and therefore also to the common edge of planes $\pi$ and $\pi$.

Line $PE$ is perpendicular to line $QR$ because the median in an equilateral triangle is also an altitude. Therefore, line $QR$ is perpendicular to the common edge of planes $\pi$ and $\pi$. Hence, the angle $\alpha$ between planes $\pi$ and $\pi$ is equal to the angle between line $QR$ and its projection $QR$ on plane $\pi$. Thus, $\alpha = \measuredangle RQR$.

Using the Pythagorean theorem, we calculate that $QR$, i.e., $QR$. Therefore, $\tan \alpha = \frac{RR$. From the tables, we read that $\alpha = 54^\circ45$.

Similarly, we prove that the angle between plane $\pi$ and any face of the cube is also equal to $\alpha$. | 5445 | Geometry | math-word-problem | Yes | Incomplete | olympiads | false |

LII OM - I - Problem 3

Find all natural numbers $ n \geq 2 $ such that the inequality

holds for any positive real numbers $ x_1,x_2,\ldots,x_n $. | The only number satisfying the conditions of the problem is $ n = 2 $.

For $ n = 2 $, the given inequality takes the form

Thus, the number $ n = 2 $ satisfies the conditions of the problem.

If $ n \geq 3 $, then inequality (1) is not true for any positive real numbers. The numbers